Think Forward #11: Three places to look for AI's education impact

Changes already underway that technological breakthroughs could accelerate

It’s a truism that public education systems resist transformation by technological change. Instead, they domesticate new technologies for their existing processes.

Boosters and skeptics are now debating whether artificial intelligence will join the long list of technological advances that were subsumed by the existing conventions of schooling, or whether it has the potential to become the first new technology since the printing press to fundamentally transform education.

One useful way to cut through the noise is to look at changes already underway that AI has the potential to accelerate. Here are three:

1. Talking tutors

The question about whether automated tutors can improve student learning was answered in the affirmative years ago.

The questions now being explored by researchers (including those at Arizona State and Carnegie Mellon universities) deal with issues like how to effectively integrate tutoring software into schools, and how to make it useful in subjects, like writing, where computer programs struggle to interpret student work.

There’s evidence that automated tutors work in subjects like math, computer science, and foundational literacy, where a computer can evaluate simple right-or-wrong answers. An equation is solved correctly or it isn't. A string of code works properly, or it doesn't. A student has correctly identified the letters on the screen, or they haven't.

This is where the class of AI fueling the current buzz — the large language models like GPT-4 and Google’s Palm2 — could make a difference.

Because, as John Bailey has put it, language is the interface, tutors powered by these models could potentially evaluate answers and give feedback on a wider range of student work.

In addition, if massive online courses could be dismissed as talking textbooks, AI-powered tools like Kahnmigo have the potential to power talking textbooks that can hear students talk back — answering their questions or listening to what they have to say and then probing with questions of their own.

In other words, advances in AI might expand the range of subjects where automated tutors are useful, and make them more interactive for students.

2. Shifting the role of human educators

School closures during the Covid-19 pandemic spawned hundreds of experiments that blended online teaching with in-person support.

While “remote learning” often received poor reviews from students and teachers alike, it brought some benefits.

Students could work at their own pace. Families could travel the country and remain connected to school. Adults other than traditionally certified teachers — including some who might have more in common with the students, like parents or after-school staff — could work directly with students during the school day.

When most of the core academic content is delivered through an online learning platform, the role of the adult in the room with the student — often called a coach or a guide — can shift from content expert to troubleshooter, motivator, and relationship builder.

Learning providers like Prenda, KaiPods, and Great Hearts' microschools are experimenting with different ways to improve on this basic design.

A teaching team of the future, conceived by Bing Image Creator

These models open the door to new contributions from parents, community educators, or other people who lack formal teaching credentials but bring other benefits to the table — like a strong relationship with the students or a passion for sports or art or carpentry that can motivate young people and enrich their learning.

It’s possible to imagine an AI-powered online learning platform working in concert with these contributors.

3. Teachers’ new teammate

Wharton School Professor Ethan Mollick argues that large language models have little in common with modern computer software, due to their creativity and empathy, but also their unpredictability and susceptibility to delusion. It can be helpful to think of them as people.

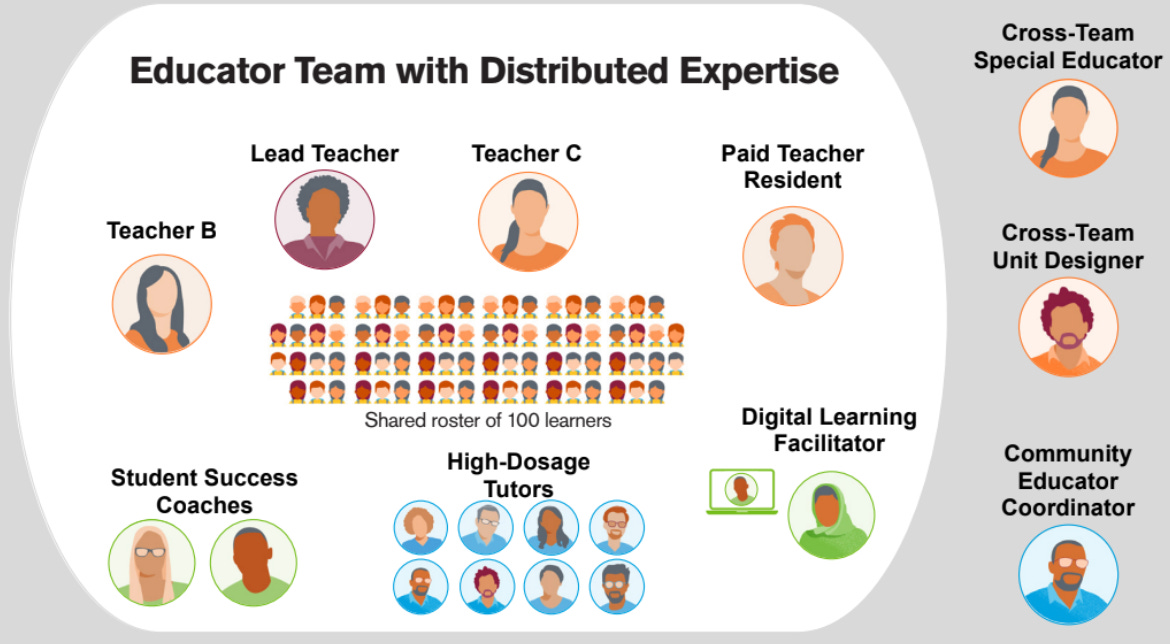

Our ASU colleagues designing the Next Education Workforce have created graphics illustrating new teaching teams that could replace the one-teacher, one-classroom model. What would it look like if a robot joined this team?

The robot could work as a tutor or curriculum curator, freeing the adults to work one-on-one with students and design learning experiences. It could also work as an assistant — helping human colleagues plan lessons, curate curriculum materials, or grade assignments.

Bottom line: None of these sounds like wholesale transformation of education as we know it. But each is plausible because, to some extent, it’s already happening.

Think Fast

Writers from Matthew Yglesias to the Washington Post’s Perry Bacon Jr. are musing about what to make of the slow death of the bipartisan education reform coalition. All the columns in this genre struggle to articulate any coherent vision for what to do now.

Mike McShane argues a positive vision for the future of education was on display at the late April conference hosted by the National Hybrid Schools Project. I was there too, and the room was packed with entrepreneurs creating learning environments that defy conventions of schooling. I think he’s right about at least one thing: this was one of the few education conferences I’ve attended recently where the vibes felt good and the people assembled felt like they had momentum.

Many of the learning environments represented in that room would confound education pundits and researchers. We know very little about how their kids are performing on standardized tests, for example, and their small size and unconventional structures often render that sort of measurement meaningless.Pradyumna Prasad offers a useful analogy from India, where many of the statistical measurements American government officials take for granted, like rates of unemployment or inflation, often elude leaders of a nation of 1.4 billion people spread across 1.3 million square miles. Three points from Prasad’s essay seem relevant to this new era in education — what McShane refers to as “the next storm.”First, the “libertarianism of necessity.” Authorities should be cautious in their attempts to govern things they don’t understand.Second, the importance of building institutions and infrastructure despite that uncertainty. Third, new institutions built by a nation like India need not mimic the institutions their counterparts in the West built decades ago. Leaders have an opportunity to think anew, to design solutions for their unique context, and to potentially leapfrog more developed nations by building institutions better suited to the modern world.

Michael Horn makes a similar point: Wholesale “system transformation” may be a pipe dream in American education. It won’t unfold according to anyone’s master plans. But we can hypothesize key parts of the emerging system, build accordingly, and learn as we go.

CRPE’s decades of research and thinking on school choice and education governance has led us to hypothesize some key components of the new system: navigators, bottom-up accountability, and support systems for independent educators.

Speaking of insights from India: A new paper reveals an unexpected benefit of conventional schooling. It helps build “cognitive endurance,” or the ability to concentrate on mentally demanding tasks for long periods of time. Source.

Final Thought

It will be a bit like the world of classic Star Trek, where Spock just goes to the computer, talks to it, and it tells him whatever he wants to know. Imagine if your university could do something like that.

- Tyler Cowen, of George Mason University, on one way AI might make institutions radically more efficient.