Think Forward #2: Bottom-up accountability

What if we focused on giving families the information they need to make informed decisions?

The pandemic shined a new light on an old problem: Parents aren’t getting clear, timely information about where their children stand academically, in a format that can help them make decisions.

Surveys show parents’ perceptions are more rosy than state or national test results suggest. Few are sending their children to optional tutoring or other catch-up opportunities. Grade inflation means parents might be getting mixed signals about how their children are doing.

Candace Fish saw this problem when she left her job as a public school teacher to start a microschool during the pandemic. In a recent podcast interview, she described spending her school’s first nine weeks addressing students’ learning gaps — and explaining those gaps to their parents.

"We had kids come in as seventh graders, but really, they were at about a fourth-grade level when we did math assessments,” she said. “Well, the public school didn't tell them that."

A similar problem appears in Emily Hanford’s reporting on failed approaches to reading instruction. During the pandemic, parents who had received notes home praising their children’s reading logged onto Zoom and watched students hopelessly guessing at words on a page.

Accountability in public education has long been top-down, focused on measuring schools’ results and assigning consequences — not on making sure every parent has a clear and honest picture of their child’s progress.

The pandemic exposed this flaw. It also spurred demand for new learning options that strain top-down approaches to measuring school quality.

Microschools often operate as subcontractors for larger schools, or serve groups of students that are too small to render meaningful data. New policies—like those passed last year in Kansas, which allow students to enroll in multiple schools part-time, or earn course credit for learning outside of school—enable students to receive public education from multiple institutions, complicating the question of which institution should get credit for their results.

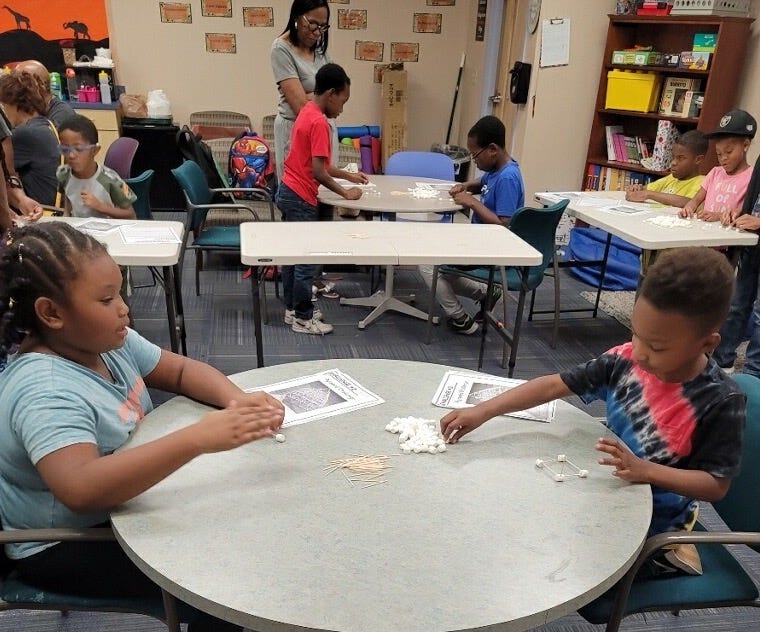

Microschools, like this one created by the Black Mothers Forum in Arizona, break conventional assumptions about performance measurement in public education.

A bottom-up approach to accountability would prioritize giving parents information that helps them understand what their children need and identify learning options that meet those needs.

Giving families accurate and actionable data on their children’s progress would be an essential starting point. There are other steps states and local communities can take to help parents plan their children’s educational trajectories and make course corrections along the way.

Five years ago, when CRPE began grappling with how to measure progress and ensure quality in a world with more unconventional learning options. Paul Hill laid out some ideas:

Define “gateway” skills. States and localities should define the set of skills that every student needs to master by age 14. That way, parents and educators can assess whether their students are on track to explore a diverse range of college and career possibilities.

Ensure career-based learning options deliver. Parents and students weighing a career education option should know up front how it will affect their future education and job prospects—and whether it will lead to the opportunities it promises.

Support students with navigators. Students and families should not be on their own to assemble the right set of education options for their children. Navigators build relationships with students and their families, and help them set goals and find learning options that fit their needs.

The pandemic revealed gaps between what many students and families were promised by their schools and what they were getting. Bottom-up accountability would give them tools to know the truth.

Think Fast

Four-day school weeks continue to spread. Once largely confined to rural Missouri districts, the contagion has reached larger districts in the Kansas City metro area. The unstructured fifth day hurts some students’ learning and creates a potential hardship for families who must provide their own childcare. But it also creates a blank slate for communities to create new and different learning options. Policymakers in states like New Mexico and Oklahoma are looking to slow the trend. Rather than ban four-day weeks outright, they could encourage experimentation. Require districts that shorten their weeks to offer families “fifth-day funds”—flexible spending accounts they can use for transportation, tutoring, enrichment or childcare options of their choice.

A microschool founder offers a novel analogy for creating new learning alternatives outside public education, while also advocating for change inside the system: Remove the fish to clean the tank.

Isolation was one of the biggest challenges reported by educators in learning pods. In regions with a critical mass of education entrepreneurs, collaborative communities are starting to form. In South Florida, the entrepreneurial ecosystem includes an array of new learning options beyond schools.

Provocative advice on how to think about the educational implications of artificial intelligence: “Instead of insisting on top-down control of information, embrace abundance, and entrust individuals to figure it out. In the case of AI, don’t ban it for students — or anyone else for that matter; leverage it to create an educational model that starts with the assumption that content is free and the real skill is editing it into something true or beautiful; only then will it be valuable and reliable.”

Final thought

“This is the last moment of normalcy—and no one's paying attention, because most people don't understand exponential curves. It was such a strange feeling, and I've often thought about the parallels of that moment, that hit so viscerally, with AI.”

- OpenAI founder Sam Altman, reflecting on a night walking home in early spring of 2020, seeing neighbors oblivious to the nascent global pandemic. Most of us don’t see paradigm shifts until it’s too late. Food for thought in 2023.